Magnesium – Are You Deficient?

June 7, 2023

Written by: Stephen Blankenship

Share on:

This article is Part-I of a multi-series educational blog on magnesium. Magnesium (Mg2+) is a natural mineral present in the human body and is essential to health. Because magnesium plays a role in so many critical functions, the body has complex management mechanisms. Magnesium is the subject of hundreds of studies and literature reviews. In this article we will examine the contributing factors to magnesium deficiency and the complications of diagnosing magnesium deficiency.

Biological Role of Mg2+

Magnesium is one of six macro-minerals and is essential for humans. The other five major minerals are calcium, sodium, potassium, phosphorous, and chloride. Magnesium is the fourth most abundant mineral in the human body and second most abundant intracellular cation, after potassium.

Magnesium acts as a cofactor in more than 600 enzymatic systems that regulate metabolic and biochemical reactions.[1] Magnesium cofactors regulate the function of enzymes that are responsible for numerous cellular processes, which are summarized below.

- Supporting the metabolism of the other macro-minerals in addition to glucose, acetylcholine, and nitric oxide.

- Supports electrolyte balance through intracellular homeostasis.

- Required for the activation of Thiamine.

- Important to the structural development of bones.

- Required for the synthesis of DNA, RNA, and protein.

- Supports nerve impulse conduction and muscle contraction.

- Important cardiovascular regulator.

- Modulates inflammation and oxidative processes.

- Required for the formation and activation of adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

- Neuronal magnesium concentrations are essential for learning and memory.

The human body contains approximately 25 grams of magnesium, which equates to 4-6 teaspoons. Most of your magnesium concentrations are found in your bones and soft tissues and compose 50% to 60% of your total magnesium. Only 1% of total magnesium is in the blood serum. Normal serum magnesium concentrations range between 0.75 and 0.95 millimoles (mmol)/L.[2]

The current Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) for magnesium in adults 19 years of age and over is between 310mg and 420mg depending on gender.[2] The World Health Organization has estimated that 75% of Americans do not meet the Recommended Daily Intake (RDI) of magnesium.[3] Many medical researchers find the RDA figures inadequate to prevent deficiencies of magnesium and chronic disease.[4] Data on dietary habits reveal that intakes of magnesium are lower than the recommended amounts in both the United Sates and Europe. The most recent published review on magnesium concluded: “Approximately 50% of Americans consume less than the estimated average requirement (EAR) for magnesium, and some age groups consume substantially less.”[5]

Magnesium Deficiency

Hypomagnesemia is the clinical term used for magnesium deficiency. Today, hypomagnesemia is a common condition among the general population.[6] Since blood serum magnesium does not reflect intracellular magnesium, most cases of magnesium deficiency are undiagnosed. Given the importance of magnesium in the functioning of many reactions in the human body, this deficiency can increase the risk of physical and mental health illness over time. “The evidence in the literature suggests that subclinical magnesium deficiency is rampant and one of the leading causes of chronic diseases including cardiovascular disease and early mortality around the globe, and should be considered a public health crisis.”[7] Magnesium deficiency can be caused by inadequate diet, lifestyle conditions, pharmaceuticals, physiological conditions, and pathological conditions. Let’s examine some of the causes of magnesium deficiency.

Dietary Factors Contributing to Magnesium Deficiency

The typical America diet, which is rich in saturated fats, high in sugar intake, and full of phosphates not only causes magnesium deficiency but increases the need for magnesium in the human body. The following dietary factors contribute to magnesium deficiency.

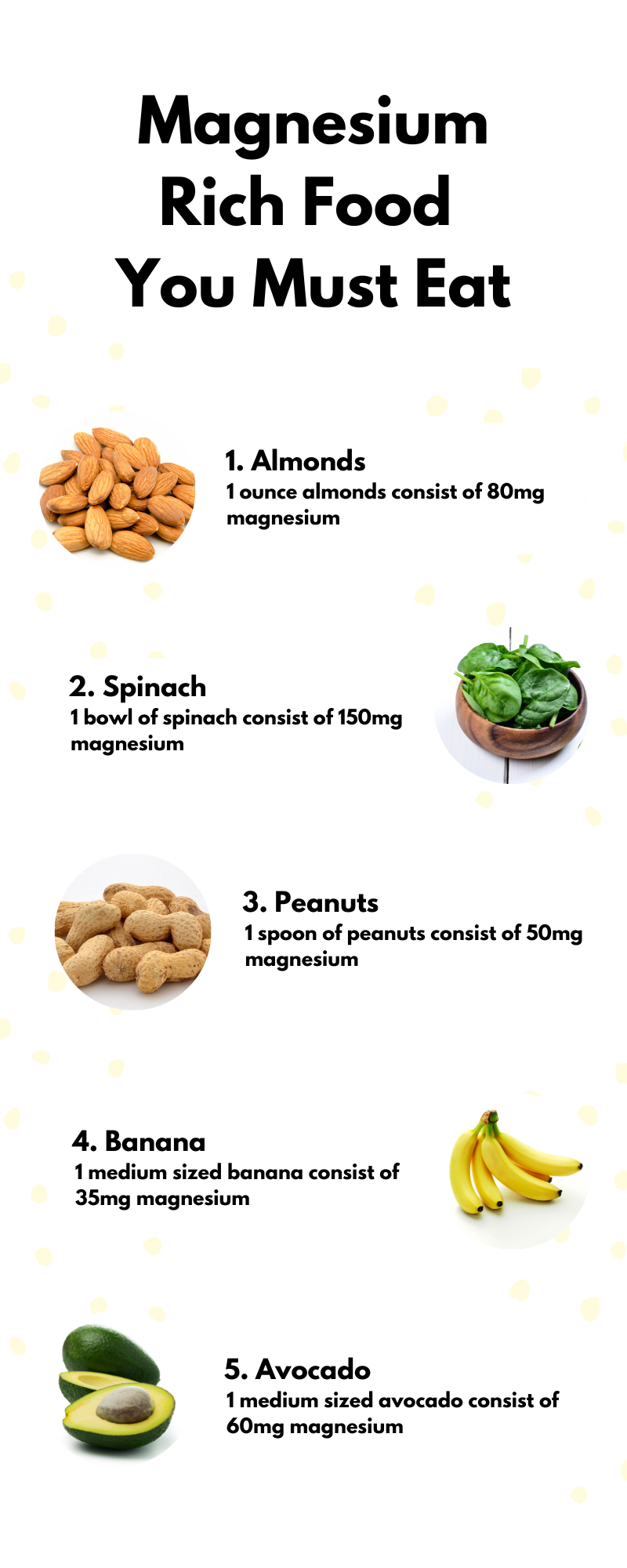

- Lack of incorporating magnesium rich foods. There is also evidence to suggest foods once rich in magnesium, now contain lower amounts due to topsoil erosion, soil exhaustion, and refinement processing. Furthermore, changes in cultivation practices have also decreased the mineral content in foods.

- High doses of zinc can decrease magnesium balance.

- High caffeine intake.

- Alcohol consumption.

- High calcium intake.

A high phosphorus to magnesium ratio can reduce magnesium absorption.[7] A major source of phosphorus is represented by soft drinks. Dairy, specifically cheese, has a high phosphorus/magnesium ratio.

Dietary aluminum has been shown to reduce the absorption of magnesium five-fold, reducing magnesium by 41% and causing a reduction of magnesium in the bone. Aluminum use is widespread and can be found in cookware, deodorants, over the counter and prescription drugs, baking powder, and other baking products.[7]

It is postulated that foods high in phytates can lead to nutrient deficiencies through binding by phytic acid. This is a misconception in the case of magnesium because urinary magnesium excretion will drop to compensate for the reduction in bioavailable magnesium.[7] Foods high in phytates also happen to be rich in magnesium therefore it is unlikely that consuming foods high in phytates would contribute to magnesium deficiency.

It should also be noted that water can be a good contributing source of magnesium. However, magnesium is absent in soft water and therefore should not be considered as a contributing source.

Lifestyle Factors Contributing to Magnesium Deficiency

The relationship between magnesium status and exercise has received significant research attention. Research has shown that marginal magnesium deficiency impairs exercise performance. Strenuous exercise increases urinary and sweat losses that may increase magnesium requirements. Magnesium intake less than 260 mg/day for male and 220 mg/day for female athletes may result in a magnesium deficiency.[8] Also important to note is that magnesium supplementation in individuals with adequate magnesium status has not been shown to enhance physical performance.

One third of U.S. adults get less than seven-hours of sleep each night. A National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey showed that participants with short sleep duration had a lower intake of magnesium and other nutrients.[9] This does not conclude that short sleep duration is causation of magnesium deficiency however this does demonstrate a correlation with magnesium deficiency, emphasizing the possible need for dietary supplementation for people who do not get adequate sleep.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that magnesium plays an inhibitory key role in the regulation of the normal stress response. Low magnesium status has been reported in several studies assessing nutritional aspects in subjects suffering from psychological stress. The results suggests that stress could increase magnesium loss causing a deficiency and in turn, could enhance the body’s susceptibility to stress, resulting in a magnesium and stress vicious circle.[10] Stressful conditions increase the body’s need for magnesium and may reduce stomach acid levels. Magnesium’s bioavailability is vulnerable to a reduction in hydrochloric acid because most forms of magnesium must be broken down by stomach acid before they enter the small intestine where absorption occurs.

Pharmaceuticals That Contribute to Magnesium Deficiency

Certain prescription medications such as diuretics, antibiotics, painkillers, cisplatin, and proton-pump inhibitors can deplete magnesium levels in the body by either blunting absorption or by increasing urinary excretion.[11]

Physiological Factors Contributing to Magnesium Deficiency

Magnesium deficiency is prevalent in women of childbearing age and the need increases during pregnancy. The requirements of magnesium in pregnancy are not well understood but blood serum magnesium has been shown to decrease during pregnancy. Optimum magnesium levels are essential for the health of the mother and the fetus during pregnancy and for the health of the child post-partum.[12] Given that roughly 75% of U.S. adults consume less than the recommended daily allowance of magnesium, it is very likely the majority of pregnant women are not meeting the recommended intakes of magnesium and should be counseled to include dietary magnesium or supplementing with a magnesium supplement.

Magnesium deficiency is involved in a large range of medical conditions that could compromise the elderly’s health. Studies conducted on elderly patients have demonstrated magnesium’s critical role in maintaining bone health, adequate glycol-metabolic health, and correct cardiac and vascular function.[13] Older adults are more likely to have chronic diseases or take medications that can alter magnesium status. Older adults also have lower dietary intakes of magnesium than younger adults.[14] A literature review of 37 articles discovered that magnesium deficiency was a possible public health concern for older adults.[15]

Pathological Factors Contributing to Magnesium Deficiency

Many metabolic conditions have been linked to magnesium deficiency. People with gastrointestinal conditions are at risk of magnesium depletion over time due to malabsorption issues. These include Crohn’s disease, irritable bowel syndrome, celiac disease, ulcerative colitis, and intestinal bypasses.[1]

Increased urinary magnesium excretion can occur in people with insulin resistance and/or Type-2 Diabetes leading to magnesium deficits.[16]

Magnesium deficiency is common in people who suffer from alcoholism. This disease is typically associated with poor dietary intake and nutritional status including gastrointestinal problems, pancreatitis, renal dysfunction, and phosphate depletion which all contribute to decreased magnesium levels.[17]

Summary

Magnesium inadequacy can occur when intakes fall below the RDA. Many factors can affect magnesium balance. A study conducted by Baylor University Medical Center concluded that only approximately 38% of magnesium consumed is typically absorbed by the body.[9] The conditions outlined above coupled with the fact that dietary sources have reduced levels of magnesium and that less than half of consumed magnesium is absorbed can put otherwise healthy people at risk for hypomagnesemia.

For a complete list of the potential causes of magnesium deficiency, see Box 2 of the Open Heart article by DiNicolantonio JJ, et al.

Diagnosing Magnesium Deficiency

“Magnesium deficiency is extremely hard to diagnose since symptoms are generally non-specific, there are numerous contributing factors, and there is no simple way to diagnose magnesium deficiency.”[7] Magnesium can be measured through serum total magnesium concentration (STMC), urine analysis, muscle tissue biopsy, and other methods. STMC is the predominant test used by healthcare providers to assess magnesium status.[5] The normal status as defined by the current serum magnesium reference interval is between 0.75 and 0.95 millimoles (mmol)/L. “A serum magnesium level less than 1.7–1.8 mg/dL (0.75 mmol/L) is a condition defined as hypomagnesemia. Magnesium levels superior to 2.07 mg/dL (0.85 mmol/L) are most likely linked to systemic adequate magnesium levels, as also reported by Razzaque, who in addition suggests to individuals with serum magnesium levels between 0.75 to 0.85 mmol/L to undergo further investigation to confirm body magnesium status.”[1]

Numerous literature reviews suggest that subclinical magnesium deficiency can exist despite normal status blood serum levels. This is because only about 1% of the magnesium stores reside within the blood serum. A recent literature review provides convincing arguments that an evidence-based serum magnesium reference interval is needed and “that adopting a revised serum magnesium reference interval would improve clinical care and the public health.”[5]

Symptoms of Magnesium Deficiency and stress are very similar, the most common being fatigue, irritability, and anxiety.[10] Other overlapping symptoms include:

- Tiredness

- Nervousness

- Muscle weekness

- Gastrointestinal spasms

- Muscle cramps

- Headaches

- Mild sleep disorders

- Nausea/vomiting

For a complete list of the potential clinical signs of magnesium deficiency, see Box 3 of the Open Heart article by DiNicolantonio JJ, et al.

Conclusions

Maintaining proper magnesium status in the human body is vital to your lifespan and health-span. Modern societies are at most risk for magnesium deficiency due to the Western-style diet, lack of magnesium dietary intake, and high rates of chronic diseases. Numerous literature reviews conclude that subclinical magnesium deficiency is one of the leading causes of chronic disease and early mortality around the globe. Hypomagnesemia is a common occurrence in clinical care. However, it goes undiagnosed due to the lack of education about magnesium deficiency and serum testing levels that are being based on an outdated reference interval. Most individuals will need to supplement with magnesium to maintain healthy magnesium status.

This article has been provided for educational purposes only and any recommendations are not intended to replace the advice of your health care professional. You are encouraged to seek advice from a competent health professional regarding the applicability of any recommendation with regard to your symptoms or condition.

[1] Fiorentini, D.; Cappadone, C.; Farruggia, G.; Prata, C. Magnesium: Biochemistry, Nutrition, Detection, and Social Impact of Diseases Linked to Its Deficiency. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1136. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13041136

[2] Institute of Medicine (IOM). Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary Reference Intakes: Calcium, Phosphorus, Magnesium, Vitamin D and Fluoride. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1997.

[3] World Health Organization. Calcium and magnesium in drinking-water Public health significance (who.int) Geneva: World Health Organization Press; 2009.

[4] Dean C. The Magnesium Miracle. New York: Ballantine Books; 2007.

[5] Costello RB, Elin RJ, Rosanoff A, et al. Perspective: the case for an evidence-based reference interval for serum magnesium: The time has come. Advances in Nutrition: An International Review Journal 2016;7:977–93.

[6] Pham PC, Pham PM, Pham SV, Miller JM, Pham PT. Hypomagnesemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007 Mar;2(2):366-73. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02960906. Epub 2007 Jan 3. PMID: 17699436.

[7] DiNicolantonio JJ, O’Keefe JH, Wilson W. Subclinical magnesium deficiency: a principal driver of cardiovascular disease and a public health crisis. Open Heart. 2018 Jan 13;5(1):e000668. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2017-000668. Erratum in: Open Heart. 2018 Apr 5;5(1):e000668corr1. PMID: 29387426; PMCID: PMC5786912.

[8] Nielsen FH, Lukaski HC. Update on the relationship between magnesium and exercise. Magnes Res. 2006 Sep;19(3):180-9. PMID: 17172008.

[9] Ikonte CJ, Mun JG, Reider CA, Grant RW, Mitmesser SH. Micronutrient Inadequacy in Short Sleep: Analysis of the NHANES 2005-2016. Nutrients. 2019 Oct 1;11(10):2335. doi: 10.3390/nu11102335. PMID: 31581561; PMCID:. PMC6835726

[10] Pickering G, Mazur A, Trousselard M, Bienkowski P, Yaltsewa N, Amessou M, Noah L, Pouteau E. Magnesium Status and Stress: The Vicious Circle Concept Revisited. Nutrients. 2020 Nov 28;12(12):3672. doi: 10.3390/nu12123672. PMID: 33260549; PMCID: PMC7761127.

[11] Reddy ST, Soman SS, Yee J. Magnesium Balance and Measurement. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2018 May;25(3):224-229. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2018.03.002. PMID: 29793660.

[12] Dalton LM, Ní Fhloinn DM, Gaydadzhieva GT, Mazurkiewicz OM, Leeson H, Wright CP. Magnesium in pregnancy. Nutr Rev. 2016 Sep;74(9):549-57. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuw018. Epub 2016 Jul 21. PMID: 27445320.

[13] Lo Piano F, Corsonello A, Corica F. Magnesium and elderly patient: the explored paths and the ones to be explored: a review. Magnes Res. 2019 Feb 1;32(1):1-15. doi: 10.1684/mrh.2019.0453. PMID: 31503001.

[14] Ford ES, Mokdad AH. Dietary magnesium intake in a national sample of US adults. J Nutr. 2003 Sep;133(9):2879-82. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.9.2879. PMID: 12949381.

[15] Ter Borg, S., Verlaan, S., Hemsworth, J., Mijnarends, D., Schols, J., Luiking, Y., & De Groot, L. (2015). Micronutrient intakes and potential inadequacies of community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review. British Journal of Nutrition, 113(8), 1195-1206. doi:10.1017/S0007114515000203

[16] Chaudhary DP, Sharma R, Bansal DD. Implications of magnesium deficiency in type 2 diabetes: a review. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2010 May;134(2):119-29. doi: 10.1007/s12011-009-8465-z. Epub 2009 Jul 24. PMID: 19629403.

[17] Fine KD, Santa Ana CA, Porter JL, Fordtran JS. Intestinal absorption of magnesium from food and supplements. J Clin Invest. 1991 Aug;88(2):396-402. doi: 10.1172/JCI115317. PMID: 1864954; PMCID: PMC295344.

[18] Costello R, Wallace TC, Rosanoff A. Magnesium. Adv Nutr. 2016 Jan 15;7(1):199-201. doi: 10.3945/an.115.008524. PMID: 26773023; PMCID: PMC4717872.